I worry about fire when the temp dips below zero

Russell and Winnie Minehart lost everything in a sub-zero January fire.

Duluthian and Superior residents post concern on social media about a large fire in the West End. (Screenshot)

Last night, after midnight, I scrolled through social media. Someone posted a video of a large fire taken from their window. They guessed it was near 23rd Avenue West. My heart skipped—My daughter and her partner live on the corner of 23rd Avenue West.

The fire seemed to have broken out after the 10 p.m. news cycle, so there were no updates from local news sources. The more I dug through social media, the more comforted I felt that it was not her house. (I worried about who would be harmed by this fire.) I debated calling her. I decided against it, knowing she was likely already in bed.

That same night, my weather app warned of dangerously low temperatures.

For years, I’ve been uneasy about fires when the temperature plunges below zero. My concern isn’t rooted in any scientific study I’ve read—just what I like to call "Naomi’s personal research," a mix of observation and anecdotes. When sleeping in my bedroom, I always keep a pair of shoes and a full-length robe nearby, just in case I ever have to dash outside in subzero weather.

It may seem strange to worry about fire in extreme cold—an element of destruction on one end of the thermal spectrum threatening in the dead of winter. But I have my reasons.

Three Subzero Fire Stories

Here are three fires that happened in Duluth within the past eight years, though my worries stretch further back.

On January 10, 2022, while driving to Fond du Lac Tribal and Community College, I smelled smoke as I zipped through western Duluth on I-35. Later, I learned a fire had broken out in a neighborhood nearby, with wind chills hovering at 35 degrees below zero. According to the Duluth News Tribune, “Crews were pulled out of the building at 8:02 a.m. due to unsafe conditions and fought the fire defensively. Wind chills were also around 35 degrees below zero.”

I took a photo of the aftermath of another fire in January. This fire also took place during sub-zero temperatures. Everything on that side of the street was covered in ice, including the cars. (Photo by Naomi Yaeger)

That same winter, firefighters battled a blaze in downtown Duluth on another below-zero day. They had to take turns warming up while fighting the fire. The water dousing the flames almost instantly froze, coating buildings and cars in eerie, crystalline ice formations.

The wreckage of the Gloria Dei Lutheran Church a couple days after the fire. (Photo by Naomi Yaeger)

In January 2016, a Duluth landmark, Gloria Dei Lutheran Church, burned. I recall its beautiful stained-glass windows, particularly one of Martin Luther. The Duluth News Tribune described the scene: “Up the sides of the building, the stones and bricks on the exterior of Gloria Dei Lutheran Church were slick with ice and frost— proof of the torrents of water used to extinguish an early morning fire that ravaged the church Thursday.”

Whether it was the firefighters taking an axe to the windows or the heat causing them to bust, hearing the stained glass shatter in the video accounts of the firefight on TV made me feel sick.

Thankfully, no one was hurt in any of these fires.

But extreme cold fires aren’t just something I’ve read about. My own family lived through one. *

My Chapter 24: Fire!

My manuscript is about my mother and her family. It’s kind of a memoir, though I’ve told it in the third person. Some memoirs are filled with trauma, but this one is filled with the love and resilience of a family. Of course, they endured hardships—the Great Depression, scarlet fever, WWII, serious accidents and fire—but the story focuses on how they persevered.

In January 1952, a fire raged through Avoca on a subzero night. My mother’s family, the Mineharts, lost their business and home. A whole block of Avoca burned. The Minneapolis Tribune even found it newsworthy.

Newspaper clippings from the Worthington Daily Globe (Courtesy of the Murray County Museum)

Janette had recently graduated from nursing school.

Here is an excerpt from my manuscript:

The desk phone rang.

“Murray County Memorial Hospital, Miss Minehart speaking,” she answered in a voice younger than her twenty-one years.

“Janette?” a voice said. “You better come home. The hardware store is on fire!”

If the hardware store was on fire, the family’s apartment was above it was too.

Janette’s heart raced. Where were her parents?

Since it had been an uneventful evening shift, the nurses told Janette she could leave before the 11:30 p.m. shift change.

Janette grabbed her oatmeal-colored wool coat with its fake fur collar. She had bought it with a recent paycheck and loved it. She sat down to pull her rubber boots over her crepe-soled white nursing shoes. Though she wanted to sprint to the truck and race home, she knew the bitter cold could be dangerous. Before her shift, the temperature had been five below zero; it was likely even colder now.

Outside, she spotted the family’s blue 1950 Ford pickup with Minehart Hardware painted on the doors. She pulled herself into the cab, shutting the door with a thick, heavy thud. That kind of sound only happens when it’s colder than twenty below.

Holy Moly, how cold is it? she wondered.

The truck groaned before the engine finally caught. Inside, her breath hung in the air. The plastic seat stole her warmth. Her nose burned, but pulling up her scarf would only fog her glasses. She wished she could fly to Avoca but knew she had to let the truck warm up first.

It was 11:20 p.m. when Janette approached Avoca. Parking by the train depot two blocks away, she stepped out into the freezing night.

The air smelled of burning wood, but not like a cookfire or campfire—this was dry, acrid. Crackles and pops filled the night. Five fire trucks lined Main Street. She spotted her parents and brothers, Jimmy and George. Relief flooded her as she ran to her father.

Water refused to flow from the hydrants. No one knew the exact temperature—some said it was twenty-four below, others said thirty. Whatever it was, it was cold enough to freeze everything.

Ten buildings lined that side of Main Street, and eight were burning. Flames swallowed the Minehart Hardware store, the Steak House, Spalding Café, a grocery store, two taverns, and a cream station. Some buildings were vacant, but others had apartments above them.

Someone shouted, “We better wake up the Webers!” A family who lived above the steakhouse. A fireman rushed inside to get them out.

Since the hydrants were frozen, firefighters drove trucks two blocks away to Lime Lake. They hacked through the ice with axes, pumped water into their tanks, and shuttled it back to the burning buildings.

This is the Moreland dresser. The one piece of Minehart family furniture which was saved from the Avoca fire. I took this photo in March 2017 while my mom rented an apartment at Parkwood Place for hospice care. At that time, Mom and I discussed it probably wasn’t worth firefighters risking their lives. (Photo by Naomi Yaeger)

As firemen sprayed water on the steakhouse’s windows to keep them from igniting, they asked Winifred if they could save anything from the apartment. She asked for the Moreland** dresser, a treasured piece brought from England by Russell’s ancestors. Inside was a gold bracelet*** Winifred’s grandfather had bought her in Maine.

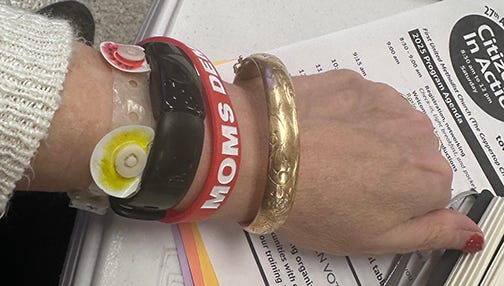

Here is the gold bracelet; it’s quite elegant but doesn’t look so good with the other things around my wrist. I don’t wear it very often, but this was an event I knew my mom and grandmother would be proud of me for attending. (Photo by Naomi Yaeger)

Janette’s brother Jim and his college roommate, Ned, had returned home that night. When they saw the flames, they ran inside to try to put them out. They quickly realized the fire was out of control. They grabbed Winifred, Russell, and George and got them to safety.

The townspeople stood in disbelief, watching the fire consume their town. A few weeks later, the community rallied, holding a “fire shower” for the Mineharts. Nowadays, they would probably start a GoFundMe account on the internet. At the “fire shower,” the community gifted them linens, household goods, and a box of rags—because rags are necessary for cleaning the house in everyday life.

Fire and cold—opposites that often meet. When winter tightens its grip, fire’s destruction can be especially harsh, reducing homes and businesses to ruins. Yet, even in the aftermath, the community and the love of family remain.

*My nuclear family had a fire that did not get out of hand on Thanksgiving Eve 1978 in Grand Forks. While the Fairleys were homesteading, a prairie fire took the life of a hired hand.

** Russell’s mother’s maiden name was Moreland. I hope to write more about the “Moreland dresser” in later Substack posts.

***I hope to write more about the history of this bracelet in later Substack posts.

So devastating. It’s amazing how fast those older homes went up in flames. It’s funny, I too have clothes by my bed in case I ever need to run out. Lately. I’ve been thinking I should have my pocket book nearby — since it has my passport and credit cards!!

My uncle was a volunteer firefighter and rescue squad asst. chief. He had a squawk box in the house at all hours when I stayed with my cousin. He was a quiet man. He crossed the English Channel on D-Day and was shot in the knee on Omaha Beach. He gave back to his country by this service to his community. My cousin, his son, became a career fireman and eventually a fire chief. There's a lot of adrenalin shooting through your veins in these situations.

Thanks for sharing these stories. Growing up my parents trained us what do in the event of a fire. If you've got a home, don't take things for granted. Have a plan.